As the battle for some 9,000 items of funding approval raged on between the establishment and pan-Democrat legislators during the past month, it is perhaps a fitting time for us to take a look at how the authorities have been presenting their planning visions over the years in such a way as to reduce public objections and lower legislative scrutiny.

Population growth – the mother of all infrastructure drivers

To build new grand projects, the authorities need to justify to the public the necessity of spending the money, and one of the most important rationales for infrastructure building is population growth – with more people we need to build more homes, more roads, more facilities, and so on.

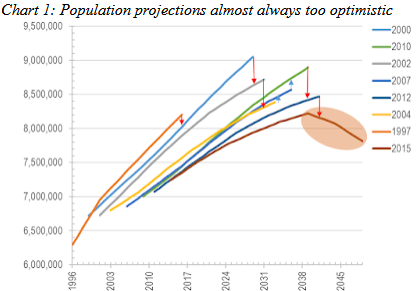

It is therefore not surprising to expect that population projections have been the most frequent victim of exaggerated projections by the government. Looking at just the population forecasts since the handover, almost every projection has had to be revised down barely a year or two after their publication. Perhaps these often wildly off-the-mark forecasts of Hong Kong’s population are the fuel that propels all near term infrastructure funding approvals!

Of the eight population forecasts between 1997 and 2015 (Chart 1 above), only two had upward revisions, and then subsequently lowered; the fact that the upward revisions happened in 2004 and 2007 are also telling – coinciding a need to spend our way out of the worst recession in living memory, as well as a change of Chief Executive, suggesting new grand spending plans for the new term of office, and therefore highly bullish population forecasts?

Further in the future, more wide of the mark

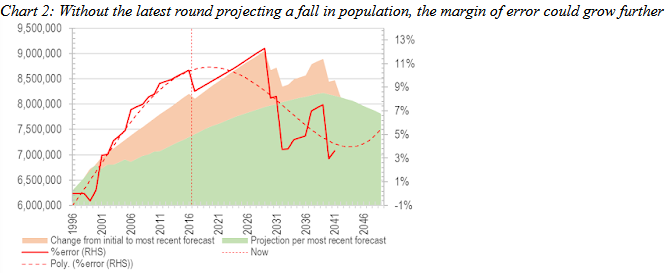

To quantify the proportional variance between the first forecast available for each year and the latest new forecast for the same period, we have plotted Chart 2 below. This shows that the ‘error’ in forecast grows gradually by the year – for example, for year 2016, the first forecast done in 1997 projected a population of 8.21m, compared to the latest forecast done in 2015 (much closer to reality) projecting 7.35million; the magnitude of errors had grown to 10% over the years. It seems the margin of error is set to increase to 12% by 2029 before diminishing.

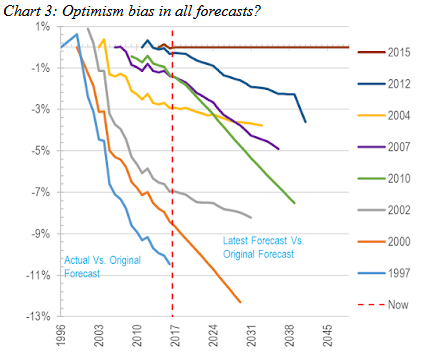

The chart demonstrates just how each year’s population projection has gone from high early estimates to much reduced latest subsequent attempts. But what about accuracy of individual forecasts? The answer is also one of general optimism bias, as shown in Chart 3 below:

The track record above suggests that almost all population forecasts have been one-sidedly optimistic, that is, the actual or latest revised figures would be anything up to 12%+ away from the correct number, often less than 20 years in the future.

One exception…

This phenomenon of optimism bias in population forecasts could be due to the mandarins being conservative, setting aside some buffer in their work to allow for flexibility in other planning initiatives. In this way, no one will blame the government for a bit of empty road where traffic flows smoothly but accusations will fly if new roads get clogged up too soon after completion owing to under-budgeting.

A more cynical interpretation of the over budgeting phenomenon might be that the civil servants deliberately mislead to grab more resources than needed so they can undertake all sorts of projects with impunity, and have an easy ride when these projects overrun on time or costs.

This scepticism could even explain why, all of a sudden, the 2015 population forecast is calling for a drop in population in 2039 (light brown highlight in Chart 1) when previous attempts have all pointed to ever ballooning numbers of citizens.

The rationale for this anomaly becomes clear when the hidden agenda is revealed – since 2015, the government has started preparing for the launch of a “Future Fund”. This means it wants our money to be put in yet another pot, managed by faceless bureaucrats, and out of the reach of the people. To persuade us that this desperately needed and for our own good, the easiest way is to show how miserable and disastrous our future would be if we were left to our own devices, that without the saintly overlords that is our government taking care of our needs from today, we would be impoverished tomorrow. Thus, the sudden bearish projections serve as an almost scientifically irrefutable proof to persuade the people of HK to endorse the establishment of such a Fund. Now we know, why blanket optimism has suddenly turned doom-and-gloom.

Case studies of past forecast misses

Turning to specific examples, we look at some live cases of how the government’s projections (or sometimes those of their highly paid consultants) have gone wrong, sometimes dramatically, in real life.

1) Image project no. 1 – the HK-Macau Bridge

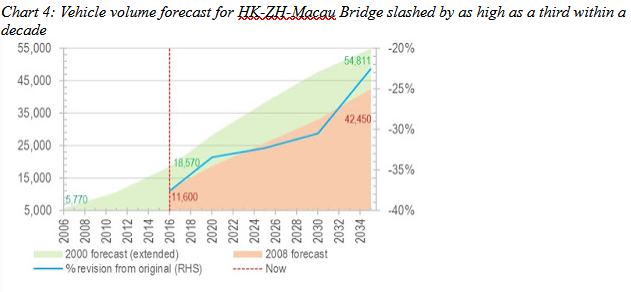

An image project is a Chinese specific term, describing where major works are not undertaken for hard utilitarian needs of the people, but for the vanity or political advancement of the cadres, whose careers are dependent on achieving very high GDP growth figures. Such growths are more easily attained when vast quantities of often unnecessary concrete is poured in the name of the people. In the case of HK, the HK-Macau Bridge suspiciously looks like one such image project, for the following reasons:

1) at HK$110 bn All in (or 4.5% of our annual economic output), this project does not include rail passengers, which should be the biggest reason why a link between the two sides of the delta is to be built;

2) the cost whilst still ballooning, and amounting to HK$140 per vehicle over the next 30 years, is met by newer and lower traffic projections, pushing the break-even fare to HK$380 per vehicle (i.e. nearly 3x!). Chances are cost revisions will rise further still, and the population and traffic projections will drop further too, leaving us with even more expensive unit rates;

3) due to lack of parking facilities, road capacity issues, and border checking complications, the authorities are already having to meaningfully curtail cross border car traffic before the project is even completed.

As can be seen in Chart 4 above, the whole justification for the bridge has gone down by 38%, or over a third(!) when the latest forecast in 2008 was published, compared to the earlier one from 2000 – even the 10% drop in population projection cannot stretch to cover the degree of over-optimism built into the earlier set of numbers. The only explanation for this gigantic variance has to be: to blow it up enough to pass funding scrutiny (and withstand cuts handed by the legislators).

2) Image project no. 2 – the Express Rail project

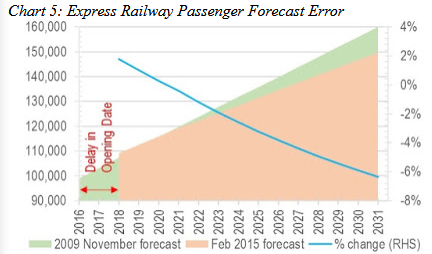

The Guangzhou-HK Express Rail project is also well known for overrunning on costs and time – expenditure has ballooned 29% from HK$65bn to HK$84bn (with government politically forced to cap at this level, leaving the MTRC to swallow further overruns by the back door) and completion timing pushed out from August 2015 to August 2017 (i.e. a 20% increase in construction times).

Besides occupying the primest piece of land in downtown Kowloon, thereby depriving astronomical revenues from land sale for other uses, the additional benefit of the High Speed Rail has been progressively whittled down by successive governments: from a trip time of 48 minutes to Guangzhou in 1998 to over one hour now (partly due to the number of stops rising from four to six, effectively turning this from a national express to a regional commuter-rail!), and seven hours for HK-Beijing to nine hours now. Compared to the existing through-train times on the East Rail of 1:54 hours and numerous buses from over 18 locations in HK and the convenience of multiple stops in residential districts along the way, the High Speed Rail’s out-of-town station (which needs connecting transport) seem all the more superfluous.

For the purpose of identifying forecast bias, it may be the case that in order to justify the cost overruns and time delays, near-term passenger projections needed to be increased (in discounted cashflow terms, this results in higher value-add in the net present value). However, it is interesting to note again that long term passenger throughput projections are being slashed in the official estimates by some 6%, despite the near-term boost, as shown in Chart 5 below:

3) Funding needs lead to boosts in forecasts

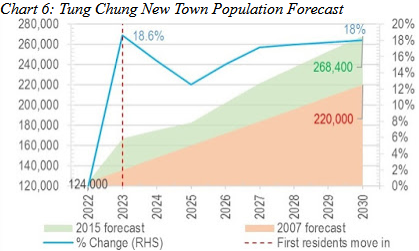

The above examples demonstrated how results will likely fall short of expectations, however, when projects have yet to be undertaken, the need to maximise budgets and resources will lead to the opposite behaviour: increasing future projections where the delivery dates are far in the future. One such example is the proposed Tung Chung New Town development which is still on the drawing boards. To maximise public money diverted to this project, the government has increased the population target/projection for 2023 by 19% between the 2007 and 2015 forecasts, as shown in Chart 6 below.

A cause of this revision was probably a 2015 Legislative Council debate on the development feasibility for the Phrase II of Tung Chung New Town. It would be imperative for the government to secure maximum resources and endorsement in the progress through the legislature and the best way to achieve that goal would be to present a rosy view of the completed project.

4) Why are we now suddenly turning uber-bearish on population?

We will recall that back in Chart 1, the government has all of a sudden started to envisage HK population decreasing starting 2039, after years of projecting never ending increases.

So what is driving this unexpected change of heart? Note that from December 2015, the government has started to express gross concern over our ageing population, and the need to prepare for the future explosion of elderlies to be taken care of by the public sector.

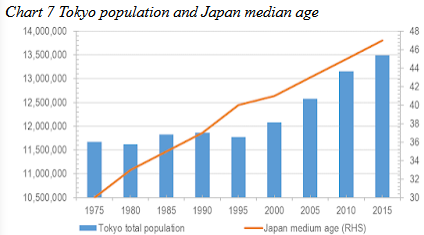

Of course, there is the first fallacy that people cannot look after themselves without the kind generosity of the visible hand, and secondly, why the opportune reversal of a long held belief in HK’s perpetual growth? As we can see from Chart 7 below, one major city with perhaps the oldest population on earth – namely Tokyo – happens to grow in absolute size pretty much non-stop in the past two decades despite having the oldest population of any major city. This immediately throws into doubt why Hong Kong will see an absolute decline, despite being a global city with its ability to attract inflows, just as Tokyo has done (despite having a more inward looking culture).

What is more, if a city can increase in size, it will be able to import the needed labour to look after its elderly population without having to resort to another form of taxation, which is what this ‘Future Fund’ must be in reality.

A further significant point that is overlooked by the bureaucrats is that longer lifespan is now affording elderly people the ability to work beyond the traditional retirement age – so instead of waiting for charity after 55, they could easily work productively into their 60s and even 70s, contributing their valuable experiences and expertise.

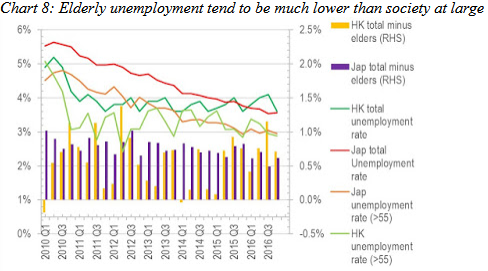

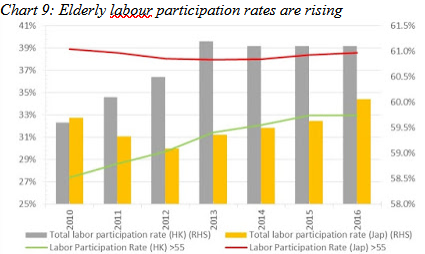

Indeed, the elderly cohort seem to have the lower unemployment in both cities compared to the population at large (Chart 8), and as we suspected, especially in Hong Kong, are witnessing rising labour participation rates (Chart 9) – if the HK population ages in the fashion seen in Tokyo, we could see our elderly participation rate (already up from 27% to 33% in the past six years) increase further towards the 39% level in Tokyo.

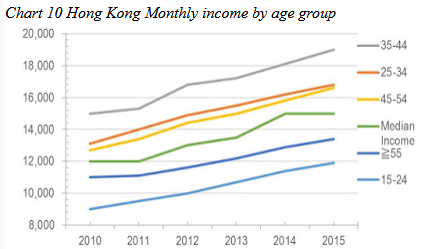

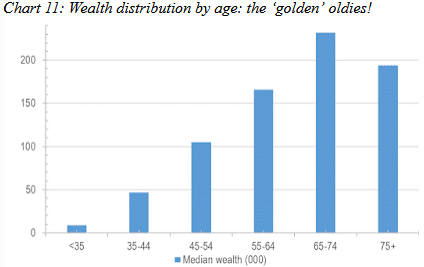

Furthermore, not only are the elderly cohort the wealthiest (HK lacks such statistics, but the US data is given in Chart 11), they are not the age group with the lowest income either (Chart 10). Of course, this income picture does not factor in the reality that the elderlies may not want to work all the time, and would prefer having leisure activities and live partly off their retirement savings.

Chart 11: Wealth distribution by age: the ‘golden’ oldies!

Chances are, as soon as the government establishes any mandatory forms of retirement welfare schemes such as a Future Fund, people will stop saving for retirement and become dependent on handouts. This is what has caused the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, where the incentive to take care of oneself has been displaced by a dependency culture nurtured through decades of high taxes and high handouts. What we should respect is that the aged workers should not be regarded as a burden but an asset, and centralising self-reliance / retirement planning into the hands of bureaucrats could turn upstanding citizens into slaves of government welfare.

The upshot of the above analysis must therefore be: with improving life expectancy, early retirement (eg. at 60) no longer needs to be the arbitrary end-point of people’s working lives. Instead of taxing the people so that they lose their ability to take care of themselves, we should encourage self reliance and family based care, for the dismantling of centuries-old family culture by the welfare mentality has done enough damage to the traditional social fabric of many civilisations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the above body of evidence clearly illustrates that government predictions are far from perfect, even objective. Mandarins are just as prone to manipulating forecasts for their own agendas. The people who pay the civil servants as well as the money they spend on our behalf should stay vigilant for every penny parted in our name. The first step to guarding our own pockets is to question every forecast assumption presented for any good causes, however well intended.

Special thanks to Mr Shen Zhenxuan (沈振翾) in assisting the collection of data and charts related to this article.

—————————————————————————————————–

Find us on Facebook or LinkedIn!