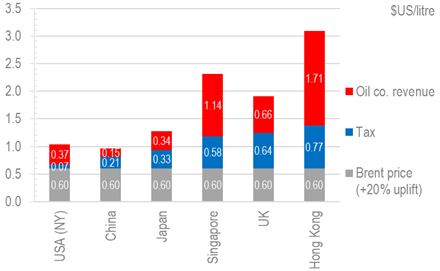

There is one thing that Hong Kong reigns supreme on global league tables – besides its high academic IB scores or long life expectancy – the city is the world’s most expensive place to buy petrol:

Figure 1: not the right reason to be named world #1?

So just how expensive is the cost of petrol to the citizens living here, and is there something that should be done about this exorbitant cost? Below we delve into the wonderful world of high land costs, oligopolies, and misdirected net zero policies to unravel this unfair set up that is likely hampering business and living costs for all Hongkongers.

Disadvantaging business vs competitors

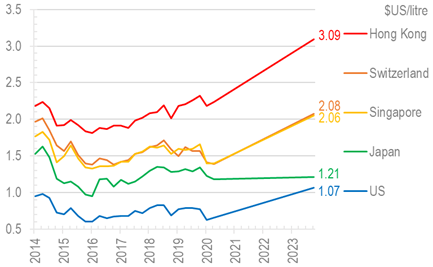

Naturally when comparing competitiveness with other jurisdictions, we turn to fellow small open economies such as Singapore and Switzerland, while also benchmarking two larger countries for added context. In this exercise we have chosen Japan (for Asia comparison) and USA (for global context):

Chart 1: absolute petrol prices – HK is head and shoulders above rest of world…

Chart 2: we pay almost 3x as much as the average US driver

According to Bloomberg/globalpetrolprices.com data, it is eyewatering how expensive Hong Kong’s petrol cost (U$3.09/litre in Oct 23) is compared to Singapore which comes in at U$2/litre, while Japan sits almost 40% lower than Singapore still at $1.21/litre. But US really rules the roost, where costs are another 12% lower at only U$1.07/litre (Chart 1). To put everything in the context of relative premium to US prices, Singapore is already at a high 92% premium, but Hong Kong for reasons we will look into below, doubles that, coming at a whopping 189% premium (Chart 2) – what is disconcerting is how the HK premium has been very steadily ranging from 150-200% since much of the past 10 years!

Petrol overpriced against premium office rent AND per capita GDP

Is this expensive fuel cost a function of Hong Kong’s high productivity or expensive land costs? Sadly not. When plotted against Grade A office rents of various top financial centres, HK really stands out in how costly its petrol is – to return to the regression norm, the price of petrol needs to plunge some 25% as a minimum:

Chart 3: HK’s high petrol costs not justified even factoring in its expensive office rents (as a cost proxy for businesses)

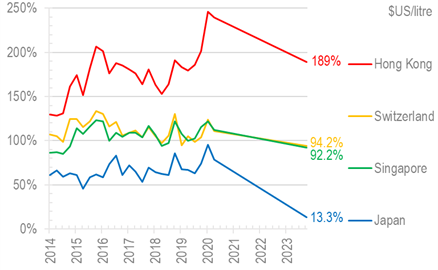

Maybe Hong Kong’s expensive real estate is a reflection of its underlying economic productivity? So we plotted the petrol costs against per capita GDP also – here the trend shows much tighter clustering around the regression line:

Chart 4: petrol costs unjustifiably high in context of our economic output

Except Hong Kong that is… Being a true outlier, our petrol prices needs to be cut an even bigger magnitude of 45% to be near the global trend line!

A double whammy of govt & big oil plundering?

To properly analyse the phenomenon of high prices, we first look at whether Hong Kong is buying more expensive international oils:

Chart 5: Import price seems to be relatively stable compared to average Brent price (and rightfully so)

It seems the spread of imported petrol over Brent price has been quite stable even though the premium does vary from teens to high 30%s in the period we looked at above. As a result, Brent oil price can be a useful approximation to the cost of gasoline for imports into Hong Kong (in the absence of dedicated granular data series thereon).

Breaking out the retail prices into its key components, we can see once more how much the consumer is being disadvantaged compared to other countries – whilst the American driver pays only 42% of hiss pump cost to the oil company and government (the rest being cost of the underlying oil), Hong Kong drivers fork out 81% in the pump price to government and oil company (Chart 7), a truly exorbitant magnitude indeed:

Chart 6: Breakdown of pump price – HK is shockingly high on tax and fees

Chart 7: The same components in % terms – HK consumers pay dearly above underlying costs

Here HK in absolute terms are even more jaw dropping – but what surprises us most is how large the profit element is that the oil company makes, after the government already takes the biggest tax chunk out of all comparable markets already (Chart 6).

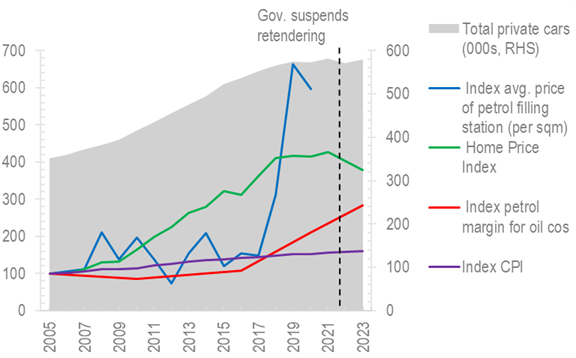

But has it always been like this, or is it something that happened recently? Looking at the past 18 years, the government levy has not moved (despite being one of the highest in the world all that time!), but it is the major spike in oil company profits that has hiked costs to the consumer:

Chart 8: Pump price – the biggest rise were in oil company margins over the past 2 decades

If we indexed the oil company margins against HK property prices it actually came in lower than home prices in the same comparison period, but something funny happened in 2018-9 period to the cost of petrol station land costs (blue line), which rose much much more (perhaps due to a combination of new entrants and the government suspension of new station tenders):

Chart 9: Comparing price of petrol filling stations; margins, and home prices

But in any case, the significant surge in recent years in oil company margins (now well above inflation index) bodes ill for consumer affordability.

Not only was the arbitrary cessation of petrol station roll out harmful to competition, as the number of cars will not stop rising as the economy and population grows in the longer term, the wishful thinking that everything can go from carbon based fuel to electric from now on (which was the basis of ending new petrol station tendering) is both unrealistic and counter-productive:

Chart 10: how likely can HK go from 85% carbon fuel to zero in 20 years?

The outright plunge by global bureaucrats towards their utopian of zero carbon targets by 2030s will create endless suffering to the people over whom they govern – a glance at the blue areas above shows how overwhelmingly dominant the global economy and people’s livelihoods are powered today by carbon sourced energy.

To impose a planned economy style hard target over the citizenry and deprive them of essential energy (red arrow) will surely return civilisation back to the stone ages – in other words, the impossibility to come up with a substitute energy capacity in such a short span of time (represented by the vertical orange arrow) means the global population, if all following this mad course of action, will be deprived of 85% of their current energy needs…

In view of the above, the HK govt should rapidly reverse its policy and start issuing new petrol station sites without delay – or consumers will continue to suffer.

A new model for petrol station licencing?

Back to the question of affordable fuel for the end user – the traditional way the HK government tenders out station sites has been on a land sale mentality – that is, with a view to selling the site areas to fetch the highest land revenue for the government and not with a purpose of creating a sustainable after market for the masses.

However, if we view petrol as an essential part of people’s daily needs, much like telephone and electricity then why should we not tender petrol stations on a different formula? Whereas the telephone exchanges and electric substations are pretty much given away for free, we submit that petrol stations should also be tendered out based on minimising future fuel costs.

The objective of controlling electricity costs is achieved by the Scheme of Control framework, which is based on return on capital invested. What we should do on petrol stations perhaps, is to have the oil companies bid for each station where the winner of the site is the one that promises the lowest price margins over the prevailing oil price at the time? Not only is this simple formula easy to monitor from an ongoing basis, it introduces a mechanism to drive down long term fuel costs and every economic sector of the society will benefit, rather than just the government’s one off land sale income. Which would you rather trust to keep the spoils from reduced oil company profits – the government or the people? The answer should be beyond dispute…

The author would like to thank Chan Hei Lui Kiandra from The University of Science and Technology majoring in Quantitative Finance for assisting in data collection and analysis of this article.