When major controversy over the appointment to the post of the pro-vice-chancellor at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) broke out in 2015, it coincided with the September publication of the QS World Univeristy Rankings (QS Rankings) showing that HKU’s academic ranking fell from Hong Kong’s number 1 spot.

This inevitably led to claims that political interference and eroding academic freedom somehow played in the drop in HKU’s ratings. Although the compilers of the QS Rankings clarified later that recent incidents would not have any impact on the rankings of universities in the 12 months prior to the publication of the results, suspicion over the link between politics and academic standards are hard to dispel.

The author takes this opportunity to delve into the underlying data of the QS Rankings and compare against a number of relevant social and economic league tables and metrics to identify any correlation between these factors and university rankings in general across the world.

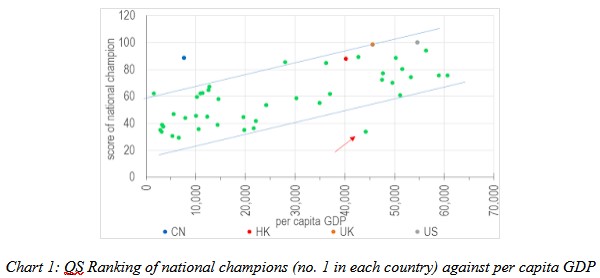

Conclusion 1: Availability of resources helps university rankings It should be common sense to link standard of education to the amount of resources dedicated to the undertaking; for example, most people would naturally expect wealthy countries to score highly in the university rankings. This relationship is clearly demonstrated in Chart 1, where the top university of countries (i.e. ranked number 1 in

in the country) with higher per capita GDP tend to score higher in QS Rankings.

It is clear from the chart above that rich countries such as the UK and USA have their top universities scoring highly within the global university community. Likewise, Hong Kong fits into the pattern with its high per capita income coinciding high scores for its top university.

There is however one significant outlier to this relationship between national output and university standards: China – this departure from the norm will be explored later on in this article. On the opposite end of the extreme to China is United Arab Emirates (red arrow), where, despite vast fortunes brought about by its crude oil industry, has not been able to fully capitalize on the resources available to raise the standards of its universities.

Conclusion 2: Rule of law, press freedom, & clean administrations deeply affect rankings

Besides financial resources, most people would intuitively regard freedom of thought as having a strong role to play in academic performances of universities. We therefore look into the various aspects of freedom of thought in this section.

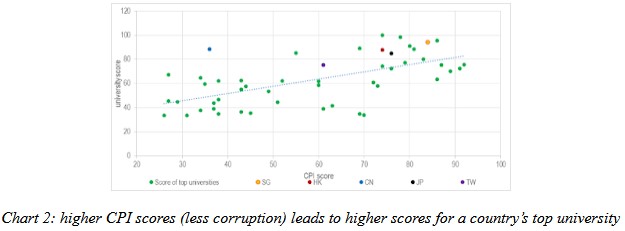

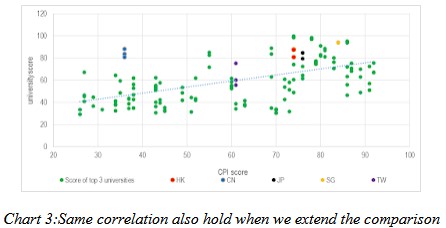

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) measures countries and territories based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived by various expert surveys. Comparing CPI scores (higher means less corrupt) with QS Ranking champion university scores reveal a pattern (Chart 2) similar to what ‘intuition’ suggested – more honest governments yield higher ranking universities. This correlation also holds when we extend the comparison to include the top three universities of each country (instead of just the number 1 entry), further supporting the thesis that low corruption results in better university quality (Chart 3).

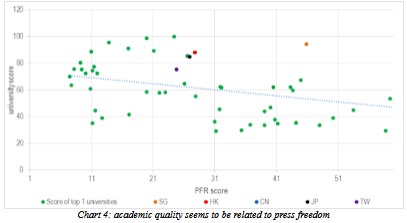

A sign of freedom of thought may be the ability to express those thoughts, and to measure this, we used the World Press Freedom Index (low score means high degree of press freedom) as a proxy. As expected, there appears to be a reasonable correlation between higher press freedom and higher university scores (Chart 4).

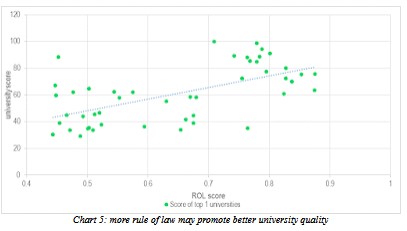

Another aspect of freedom of thought may be related to how a country plays by a clear set of rules which are fair and understood by all, as well as how the results of academic work is protected – here we compare the Rule of Law Index with QS Ranking, and the results are shown in Chart 5 above. As suspected, higher rule of law scores seem to represent countries with higher university scores.

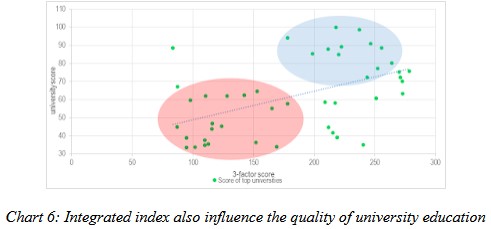

The above three indicators have some degree of commonality among them (Figure 1). We merged them into a single index and compared with university scores in a standalone exercise, the results are shown in Chart 6 below. Unsurprisingly, press freedom, rule of law and honest government all seem to contribute to the running of successful university education.

Conclusion 3: more science and engineering disciplines help lift university rankings

At the start of this text we noted the peculiar situation of China possessing high ranking universities despite the country’s low per capita GDP. This may come down to the total size of China’s economy – as long as the absolute quantum is large, there will be enough resources to focus on a national champion, and given China is the world’s second largest economy, achieving more than one national champion in the university league tables should not be an unsurmountable challenge. Besides, the high proportion of science and engineering students in China also helps its cause.

How could this be so? This may be because science and engineering subjects have far more practical areas to undertake research, and where the results are much more clearly defined, helping to score on the various university ranking metrics. In addition, many scientific disciplines may benefit from national defence related spending, and research findings here may be less affected even when the environment may be more restrictive as far as rule of law, press freedom and honest government criteria are concerned.

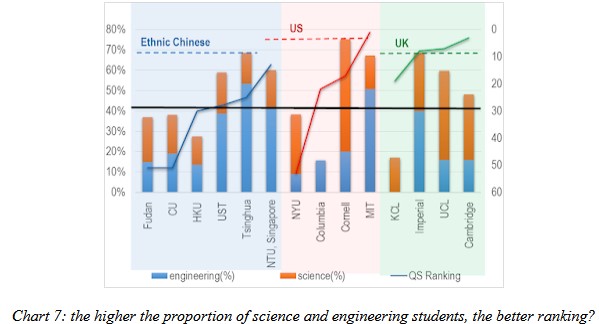

This ‘science factor’ also explains why there is a stronger presence of science/engineering schools amongst the top university ranks. For example, in Chinese speaking areas, NTU Singapore, Tsinghua, and HKUST all have over half the student body studying for science subject. This help them excel in rankings versus their more liberal arts centric compatriots such as HKU and Fudan (see Chart 7, blue shade).

The ‘science factor’ also works in USA, for example, MIT (with >60% students studying sciences) is far ahead of Columbia (less than 10%) (Chart 7, red shade). Similarly in the UK, Imperial (nearly 70% science students) also ranks higher than KCL (below 10%) (Chart 7, green shade).

Conclusion 4: Financial centres need only attract talent, not nurturing it

In order for the ‘science factor’ to excel, however, the need for supporting infrastructure can be immense (eg space for laboratories, workshops) not to mention attractive environments (New York, London are no match for Boston and Cambridge), which are in short supply in financial centres.

Even so, this has not prevented New York and London to become global financial centres despite not having the top ranked universities situated in their city boundaries – the top two universities in USA are Harvard and MIT, and the top two in the UK are Cambridge and Oxford (Chart 8).

The lesson for Hong Kong, if it is to fulfil its aspiration to be a global financial centre, is this: there is no need to set aside precious land, manpower, or financial resources to manufacture its own ‘world class’ university. By becoming a master of one – creating the right conditions to attract talent and consolidate its position as a top flight global financial centre – Hong Kong can avoid the alternative fate that being a jack of all trades entails: descending into an also-ran city.

Conclusion 5: Privately run universities excel, governments should stop meddling

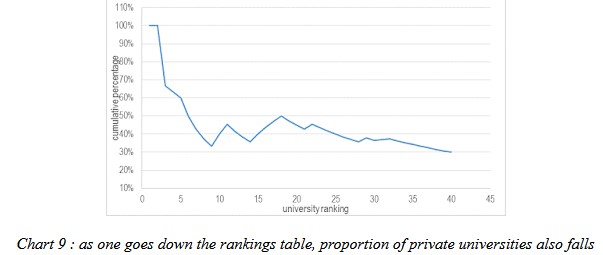

Another important phenomenon the QS Ranking tables throw up is the fact that most of the top ranking international universities are privately run, not bureaucracy managed. Starting with global number 1 ranked university down, one can see that as one descends the rankings, the proportion of government run universities increases (Chart 9). This phenomenon could be more pronounced if one excluded the fact that private institutions lack the unlimited resources of the public purse – highlighting the superior execution capabilities of the private sector.

Furthermore, this phenomenon has its parallel in the primary and secondary schools universes, where the most reputable entities also tend to be privately run. This proves the basic economic principle that no amount of bureaucratic good will is match for the proactive abilities of the private sector.

The crucial lesson to be learned by Hong Kong includes: privatise all universities, enlarge and facilitate the importation of talent schemes to encourage the best people to enter Hong Kong, as easily as Brits heading to London for the best paid jobs, or Americans seeking their fortunes in New York. Only by declaring a global war on attracting the best of the best can this city grow in an increasingly competitive world.

One of the first areas the HK government needs to dismantle barriers is that surrounding the medical profession – not only will this raise service standards in the fast falling public hospitals, reduce private sector medical bills, this move can also increase the critical mass of talent required to make Hong Kong the de facto regional (if not global) high value-add medical destination.

Final words

So what does this research exercise tell students and parents? Perhaps none. This is because the conclusion is already practised by all – they voted with their feet in entrusting their future to private universities located in wealthy, free, and low corruption countries. We merely visualised the behaviour in a series of charts.

This article was researched and written with significant input from Mr Simon Cheung, whose contribution is greatly appreciated