BNO to boost UK property, but which area benefits most?

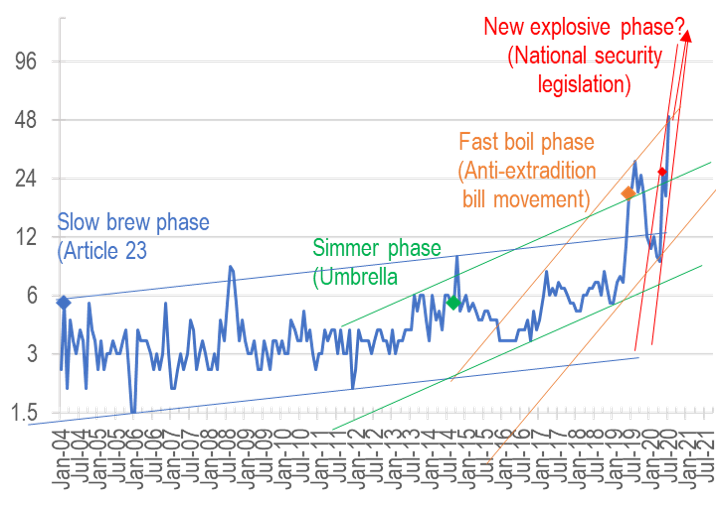

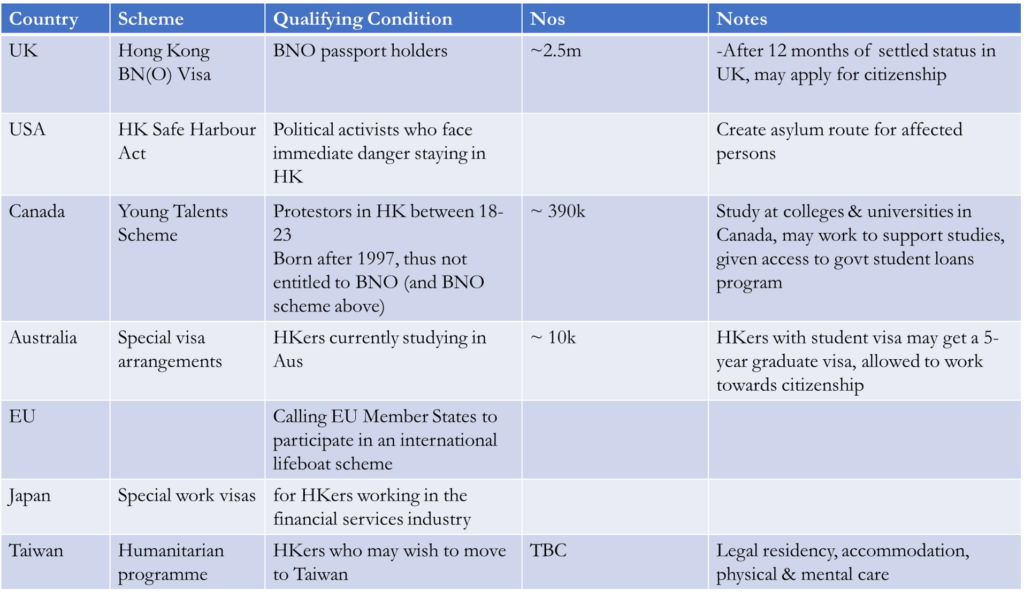

Since the imposition of the new national security law on HK from July, immigration enquiries have surged (Chart 1), while at the same time a number of foreign nations have also offered eased passage for Hongkongers to either emigrate to, or seek refuge in (see Table 1).

Chart 1: Google search of ‘emigration’ steadily rose since 2003, surging with 2014/19 protests, then hit record high with national security law

Table 1: immigration schemes announced by various Western countries targeting HKers

In this issue, we take a more granular look at how Hongkongers may impact the property market when they resettle in England (more complete data than Scotland/Wales/NI!), and from there the possible marginal impact this will have on prices.

If HKers distribute as current British Chinese in England

There are many ways to estimate where HKers will set up their new homes in the UK, for example, by income strata (but there is no easy way to get this data for BNO passport holders), or simply by how native ethnic Chinese are already distributed in the country (where census data is readily available).

The latter approach may have a skew towards country living, as more local Chinese may have already integrated into small, even rural communities, which may be harder to do for new arrivals; or there may also be a higher mix of restaurant trade operators across England which raises Chinese numbers in smaller population centres vs big cities which presumably new HKer arrivals would prefer.

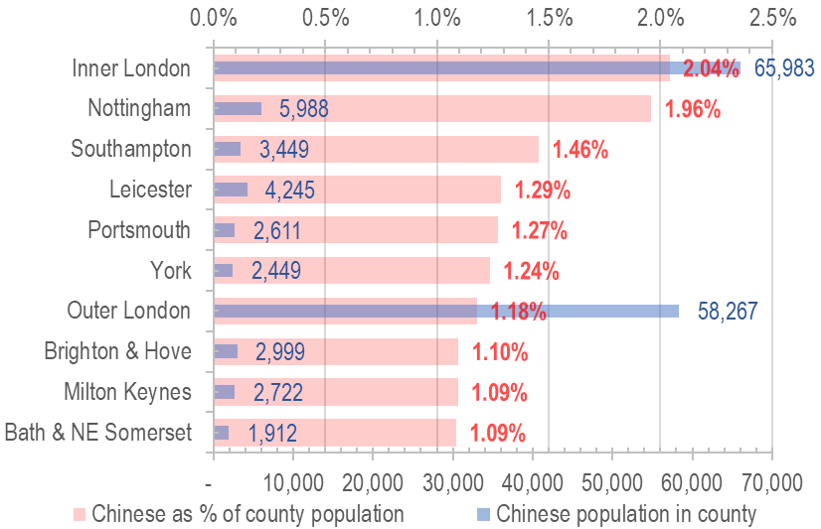

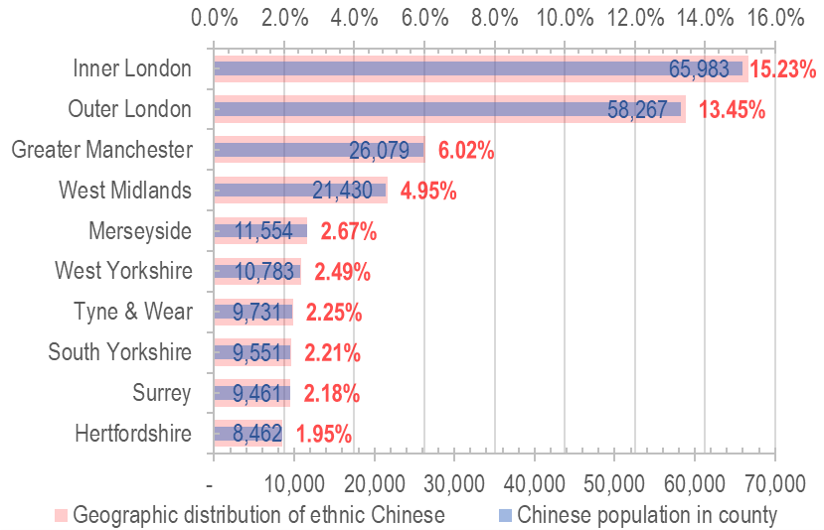

In any case, here are two useful views of how ethnic Chinese (a large proportion would be from Hong Kong) are distributed within England:

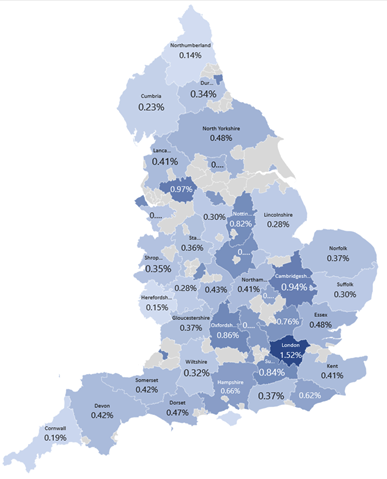

Chart 2: ethnic Chinese as % of total population in county – highest in Inner London

Chart 3: The biggest cohort of ethnic Chinese also lives in Inner London

We can infer a lot from the above numbers:

a) if 10% of the eligible HKers migrate to England, ethnic Chinese will go up by 300k from currently 433k, or a 70% increase;

b) racial tension might emerge if all 3m of the eligibles make the move – as Chinese weighting spike from 0.7% of total now to 1.2% – a big jump indeed;

c) assuming the HKers will enter England in the same proportions as ethnic Chinese currently are distributed (Fig 1 below) – which makes sense, as the current pattern already reflects the still largely ‘Hongkonger preferences’ in living in a Western host society – then some cities/counties/regions will inevitably experience more stress to their systems, from housing demand to infrastructure burden, to service requirements. Let’s now look at the housing side of the picture.

Figure 1: % pick your destination based on concentration of compatriots!

Housing shortage most severe in London, Hampshire, Nottingham?

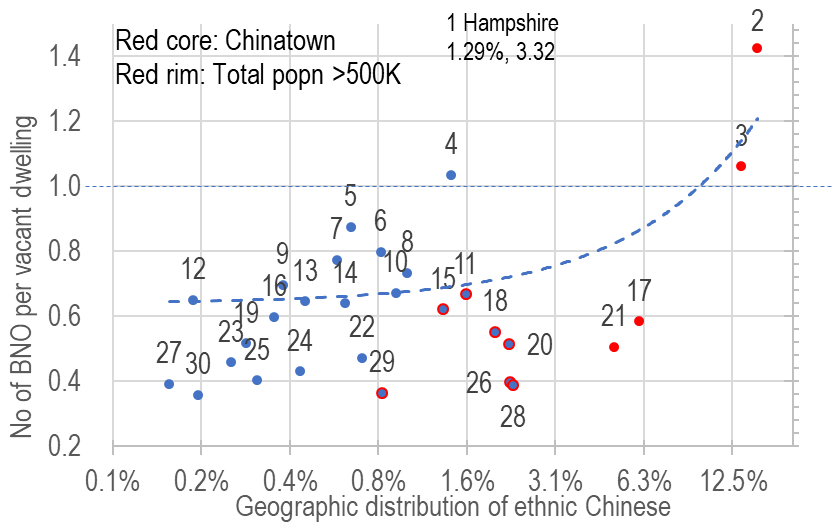

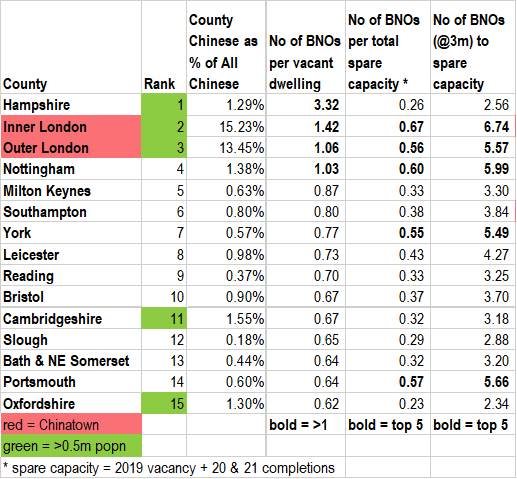

Upon arrival, the 300k HKers (allocating in same distribution as localised Chinese) will likely go for the existing vacant dwellings first, resulting in undersupply (any dot in Chart 4 with y axis value over 1) in Hampshire, London, and Nottingham:

Chart 4: new BNO demand vs existing vacancy – London, Hampshire, Nottingham most stressed

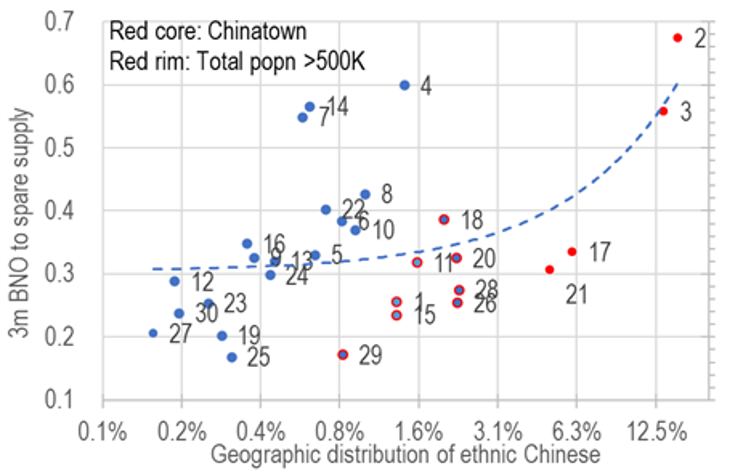

Chart 5: factoring in 2 years of supply, London / Nottingham / Portsmouth are the most stressed districts

The situation is somewhat relieved if we factor in two years of supply likely to reach market (assuming 2019 net completions can be sustained in 2020 and 2021). The result in Chart 5 follows a similar pattern, with the most overwhelmed districts being London (dots 2 & 3), York (dot 4), Portsmouth (dot 14), Nottingham (dot 7), – in that order.

In reality, significantly more than 10% of the eligible HKers may opt to take up the BNO offer, resulting in a maximum 6.7x reading on the demand:supply ratio (instead of 0.67x) for Inner London for example. This could indeed send the hotspot districts’ prices sky high indeed…

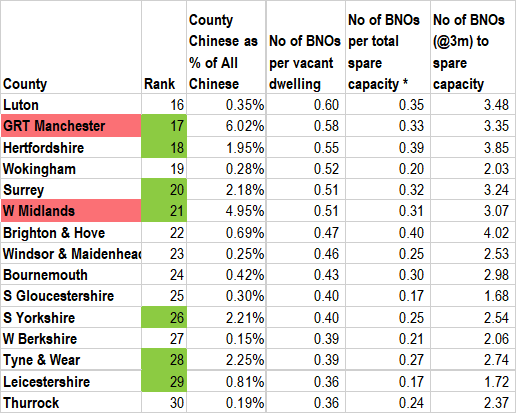

To put all of the above discussions in one concise table, here are all the details of Chart 4 and 5 laid out for the top 30 popular districts:

Other relief valves for the UK property market?

Whilst the prospect of a tsunami of Hongkongers could seem daunting at first, some other possibility may reduce such pressures – amongst them are similar migration offers made by other governments (Table 1 above). There is even the idea of ‘international charter city’, set up specifically to take larger numbers of HKers – by locating in a kind of a ‘Special Administrative Region’ that Hong Kong itself is now – the new city may even have its own tax regime and regulations.

It is almost like having a new ‘One Country, Two Systems’, but instead of being at the southern tip of China, it is moved to somewhere else in the world. For background reading on this concept see here (Chinese, more details) and here (English).

Whatever the outcome, it seems our UK strategy, which benefits from both infrastructure lifts specifically, and Brexit more generally, could see a most unexpected, and perhaps meaningful upward jolt in returns from the HK situation?