Any working couple with kids at home could recall the times when the Philippines flight bans during covid lockdowns caused a sudden shortage in helpers and pushed pay upwards of HK$8k a month for a brief period of time. In response to that symptom, the HKSAR government proposed amendments to the “Code of Practice for Employment Agencies” to reduce the ease of “job hopping” among foreign domestic helpers (FDHs).

We do not believe this rule change is the right solution (eg it infringes on freedom of labour, a fundamental human right), but take this opportunity to look at the FDH phenomenon in the context of HK’s economic set up, as well as the specific circumstances of the supply countries, hopefully identifying solutions to the shortage of staffing being reported.

Rising importance in past 30 years

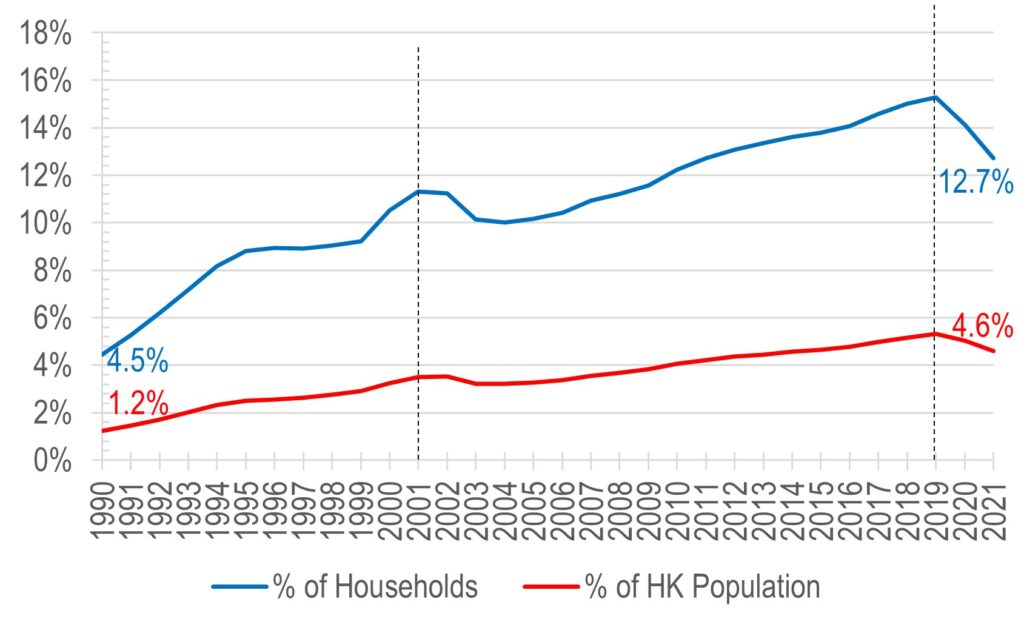

HK’s economy has increasingly relied on the importation of FDH labour presumably as more and more women entered the job market, resulting in the number of FDH rising from 4.5% of total household number in 1990 to 12.7% in 2021 (blue line in Chart 1) – a 1.8x increase in proportional terms. However, obviously more singleton families are also employing FDHs (be it elderlies by themselves or unattached young professionals), this explains why FDHs as a proportion of population has increased even more over the same period from 1.2% to 4.6% now (or a 2.8x increase):

Chart 1: Number of Foreign Domestic Helper as a percentage of Hong Kong Households

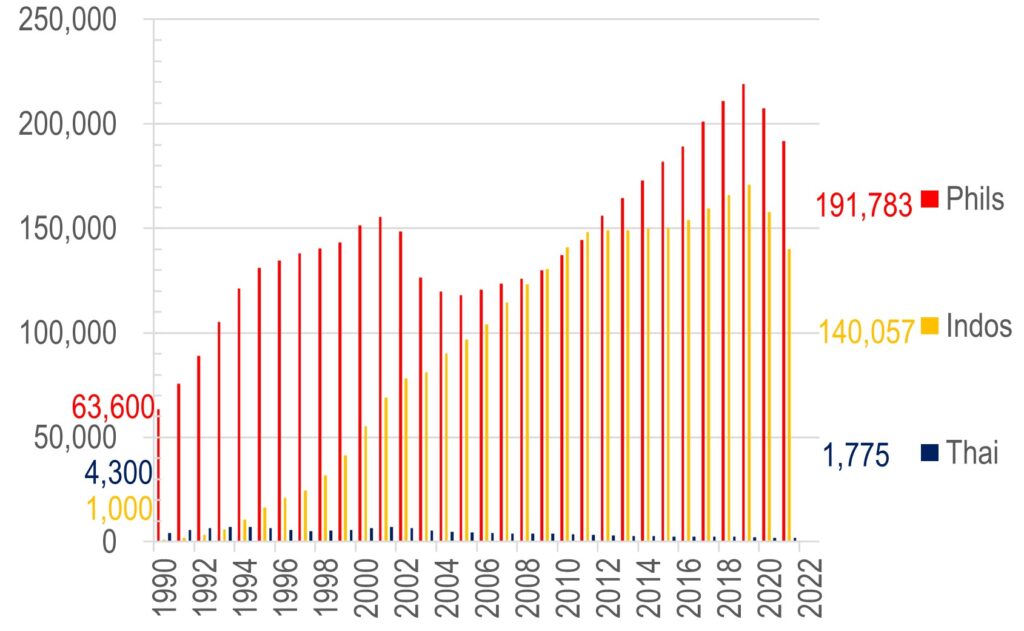

Chart 2: Number of Foreign Domestic Helpers in Hong Kong

However, this relentless increase in FDH hiring also suffered two bouts of setbacks – one after the dotcom bubble in 2001, and then another drop took place in 2019 (after the protest movement), these are marked by the dotted lines in Chart 1 above.

Within the overall trend of generally rising army of helpers, there are interesting undercurrents too – for example, against the drops in Philippines FDH in 2001-4, Indonesian reinforcements were surging that help soften the blow. This was until the protests and lockdowns of 2019-20 drove a wholesale drop in all helper populations (Chart 2).

Cheap FDH labour helped HK’s economic wellbeing

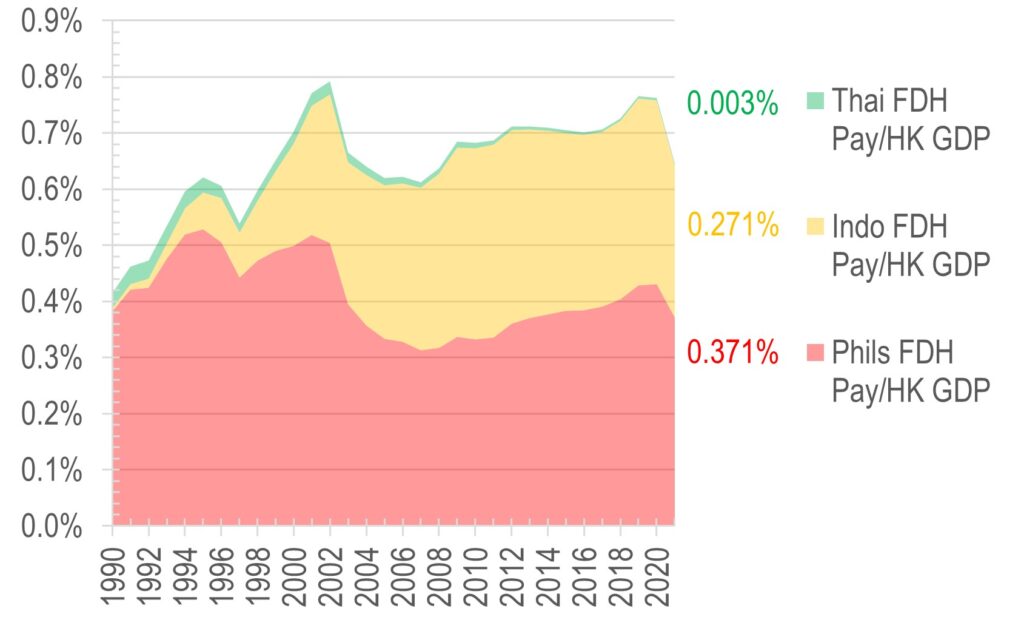

In the 1990s when the number of FDHs surged, their impact on HK’s economy, as measured by their pay as a proportion of Hong Kong GDP, was significant – doubling from 0.4% to 0.8% overall:

Chart 3: Foreign Domestic Helper salary as a percentage of HK GDP

However, their input took a dive in the 5 years that followed 2002, dropping by 23% from the prior peak. Today the top 3 helper communities together make up only 0.645% of local GDP (Chart 3).

Changing national compositions driven by economies back home

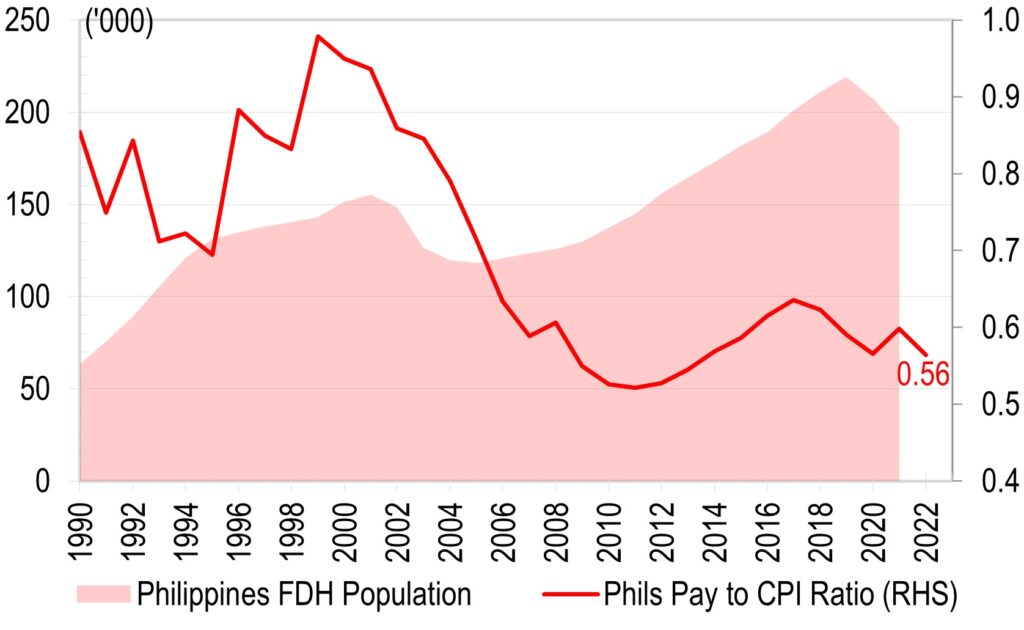

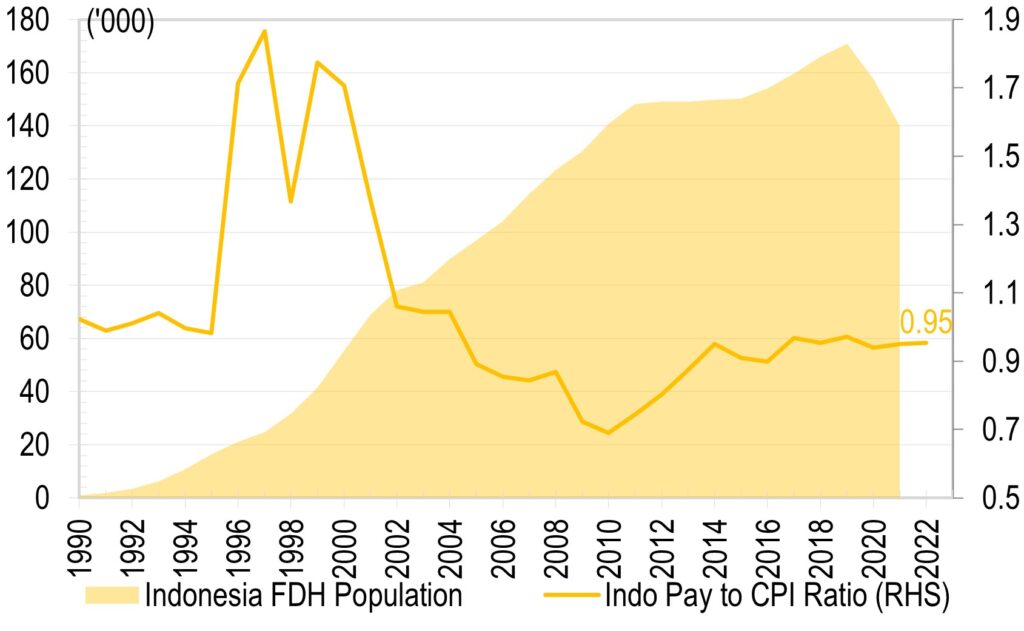

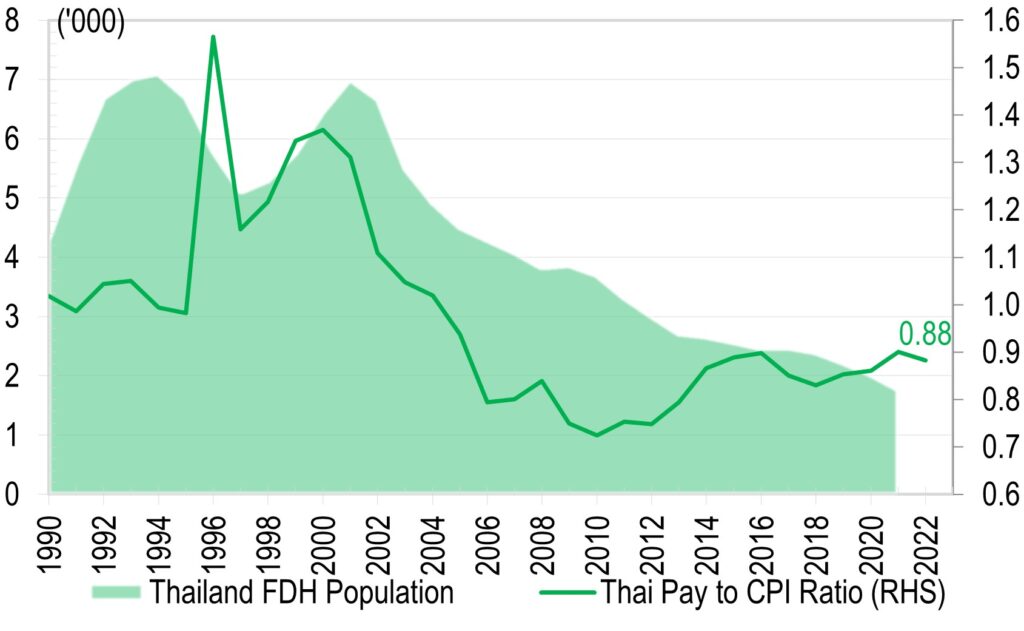

So how has HK’s attractiveness fared in the eyes of the top 3 supply countries? One thing is clear – Thai FDH supply has gone on a one way decline for pretty much the whole of the last 20 years (Chart 6) reflecting HK minimum pay underperforming Thai inflation massively since 2000. On the other hand, Phils FDH numbers have by and large increased, except during 2000-2003 when HK pay fell most against Phils inflation; and only recovered meaningfully after GFC once the pay decline has reversed once more (red line in Chart 4):

Chart 4: Philippine FDH pay relative and population of Phils in HK

Chart 5: Indonesia FDH pay relative and population of Indos in HK

Chart 6: Thai FDH pay relative and population to Thai in HK

Indo was quite different from both Thai and Phils in that despite massive pay underperformance, the absolute number of FDHs continued surging, suggesting that our minimum wage must have been rich income for the locals such that drops vs local inflation has not dented the enthusiasm with which the locals wanted to earn more income in HK (see yellow line in Chart 5).

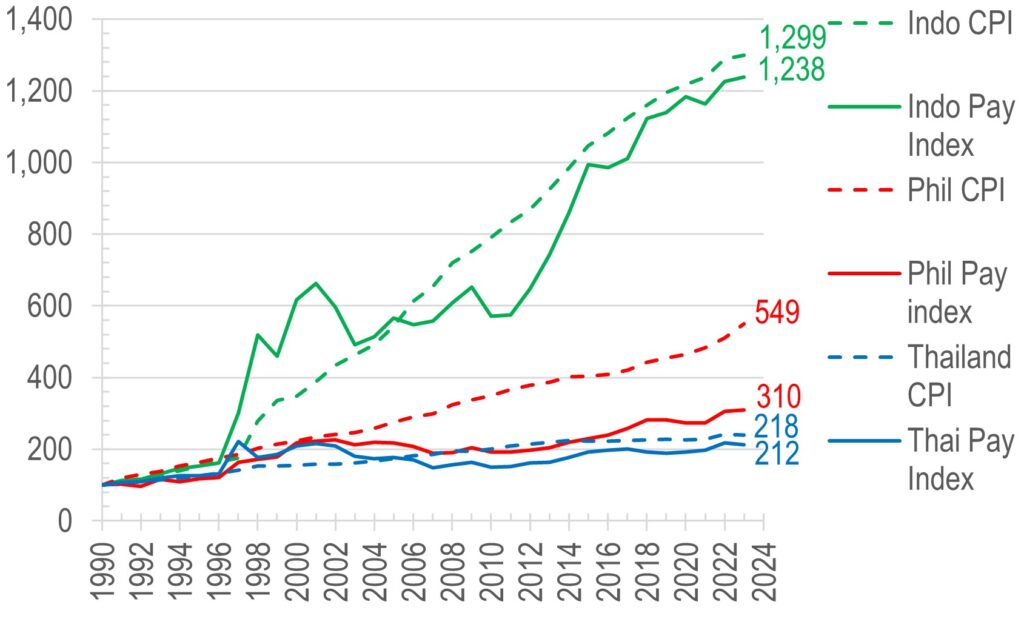

In the above charts, the ‘pay relative’ measures were arrived at using HK minimum FDH wages, translated into the local currencies back home, and divided into the local CPI, so the lines are a fair measure of how well the FDHs on minimum wages paid in HK compared to their compatriots back home. Put another way, the minimum income vs local CPI can also be expressed in separate lines, as shown here:

Chart 7: Indo/Thai pays were roughly in line with local inflation, but Phils pay significantly lost out to inflation

The above chart is also telling in that much higher Indonesian inflation over the period compared to Phils (lower by 60%) and even more vs Thai (lower by 83%) may have contributed to persistently higher FDH inflows into HK where price stability is a more important factor and USD based income considered a premium.

HKers have had it good, less so their helpers

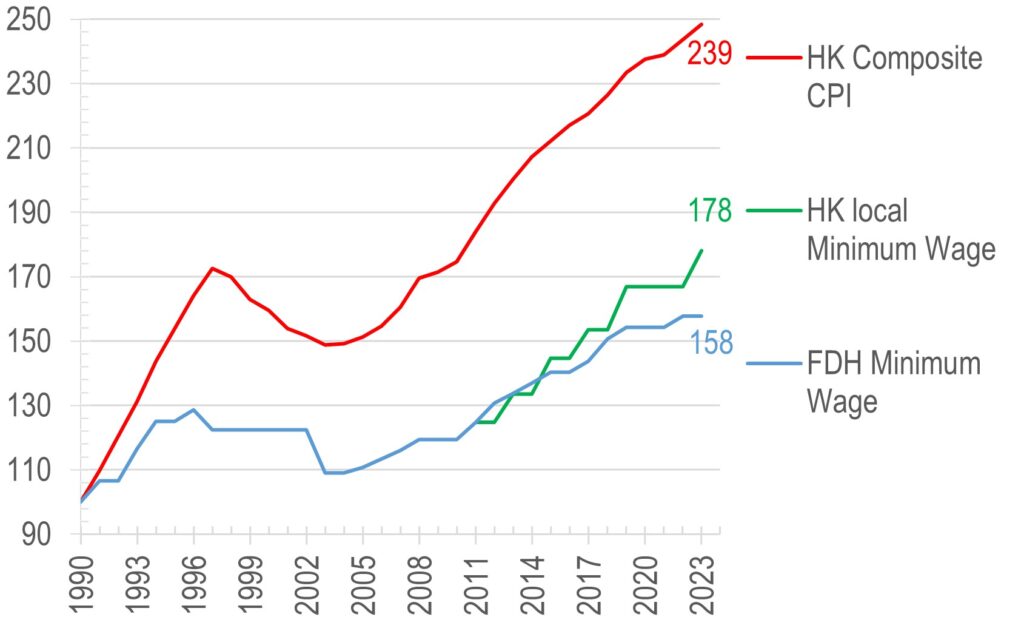

Even so, the FDH minimum wage has still lagged behind the minimum wage levels applied to local Hongkongers (see green line in Chart 8), let alone local CPI index. In fact, from the employer’s point of view, their helpers’ wage bills have only gone up 58% over the past 33 years compared to HK inflation rising some 139% over the same period:

Chart 8: FDH minimum wage lagged the equivalent standards for locals, and both lost out to inflation in turn

The above, of course are purely based on the minimum wage measure, when there are a plethora of other administrative costs that is burdening employers on top (flight tickets, insurances, agency fees and other admin costs) which seem to proliferate constantly – perhaps on top of more equitable pay adjustments for the helpers, reform should also focus on how these new forms of administrative burden can be lessened for the hiring families?

The author would like to thank Yip Kin Long Tommy from City University of Hong Kong majoring in Accounting for assisting in data collection, analysis, and drafting this article.